Archives of Depression and Anxiety

Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Hypothyroidism: A Cross-Sectional Study in Dakar, Senegal

1Thiaroye National Psychiatric Hospital, Senegal

2Fann National University Hospital Center, Senegal

3Albert Royer Children's Hospital, Senegal

4Pikine National Hospital Center, Senegal

5Center Hospitalier National Abass Ndao, Senegal

Author and article information

Cite this as

Camara M, Kaburundi D, Seck S, Gueye R, El Hadji Makhtar BA, Diack ND, et al. Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Hypothyroidism: A Cross-Sectional Study in Dakar, Senegal. Arch Depress Anxiety. 2025;11(2):025-031. Available from: 10.17352/2455-5460.000102

Copyright License

© 2025 Camara M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Abstract

Background: Hypothyroidism is frequently associated with affective disturbances; however, the burden of anxiety and depressive symptoms among Senegalese patients remains poorly documented.

Objective: This study aimed to determine the prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms and identify the associated clinical, biological, and sociodemographic factors among patients with hypothyroidism at the Abass Ndao National Hospital Center in Dakar, Senegal.

Methods: We conducted a descriptive and analytical cross-sectional study from November 2024 to April 2025 involving 40 adult patients (≥ 18 years) with hypothyroidism. Data were collected using a structured questionnaire that covered sociodemographic, clinical, and biochemical variables. Anxiety and depression were assessed by using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Scores of ≥ 8 on each subscale were considered clinically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Epi Info 7.0, with a significance threshold of p < 0.05.

Results: The prevalences of anxiety and depressive symptoms were 67% and 65%, respectively. The co-occurrence of both conditions was observed in 52.5% of the participants. Elevated TSH levels (> 4.5 mUI/L) were significantly associated with anxiety (p = 0.037) and depression (p = 0.008). Depression was also correlated with poor treatment adherence (p = 0.026) and longer disease duration (p = 0.031), whereas anxiety was more frequent among inactive participants (p = 0.037). No significant associations were found with age, sex, marital status, or educational level.

Conclusion: Anxiety and depressive symptoms are highly prevalent among patients with hypothyroidism in Dakar, and are closely linked to biochemical imbalance and poor therapeutic adherence. Routine psychological screening and adherence support strategies should be integrated into hypothyroidism management to improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Hypothyroidism is one of the most common endocrine disorders worldwide, with a particularly high prevalence among women. Epidemiological studies estimate that between 2% and 5% of the global population is affected, with a clear female predominance, ranging from five to eight women for every man [1,2].

In sub-Saharan Africa, although precise epidemiological data remain limited, several studies suggest a substantial prevalence of thyroid dysfunction driven largely by environmental and nutritional factors, including iodine deficiency, which remains a major public health concern in many regions [3,4].

The thyroid gland plays a central role in regulating the metabolism, growth, and development of multiple organs, including the central nervous system. Thyroid hormones exert profound effects on neuronal activity, influencing neurotransmitter systems that regulate mood, cognition, and emotional stability [5,6]. This intricate interplay between the endocrine and nervous systems explains the frequent association between thyroid dysfunction and neuropsychiatric manifestations, particularly anxiety and depression.

Numerous studies have reported elevated rates of anxiety and depression in patients with hypothyroidism, far exceeding those observed in the general population. Up to 40% of hypothyroid patients present with clinically significant depressive symptoms, and 30% report prominent anxiety manifestations [7-10]. This bidirectional association complicates diagnosis and management as psychiatric symptoms may obscure or mimic the classical features of hypothyroidism.

A longitudinal study conducted at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (USA) found that hypothyroid patients were 2.5 times more likely to develop depressive disorders and 3.2 times more likely to experience anxiety than the general population [11]. Conversely, individuals initially diagnosed with depression or anxiety were 1.8 times more likely to develop hypothyroidism within five years. Similarly, a large Danish-Swedish cohort study confirmed this bidirectional relationship, reporting that 42% of patients with untreated hypothyroidism developed depressive symptoms and 37% developed anxiety, whereas patients with chronic depression showed a 1.7-fold higher incidence of hypothyroidism over seven years [12].

In the Senegalese context, where access to specialized mental health services remains limited and psychiatric disorders are often under-recognized, early identification and management of anxiety-depressive symptoms in hypothyroid patients are crucial. Endocrinology departments that follow these patients provide an ideal setting for integrated screening and early intervention, helping to optimize overall treatment outcomes and improve patients’ quality of life [13,14].

The clinical relevance of this issue lies in the following three key aspects.

- Therapeutic adherence: Undiagnosed psychiatric symptoms may reduce compliance with hormone replacement therapy, a cornerstone of hypothyroidism management [15].

- Quality of life and prognosis: Psychiatric comorbidities significantly impact social and professional functioning, emphasizing the need for a holistic approach combining endocrinological and psychiatric care [16].

- Public health strategy: In resource-limited settings, such as Senegal, developing integrated screening strategies within endocrinology services could provide a model for multidisciplinary care applicable to other sub-Saharan contexts [17].

The main objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms and identify associated factors among hypothyroid patients followed up at the National Hospital Center Abass Ndao in Dakar.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

This was a descriptive and analytical cross-sectional study conducted over six months (from November 2024 to April) in the Endocrinology Department of the National Hospital Center Abass Ndao in Dakar, Senegal. The hospital is a major national referral center for endocrine disorders, providing both outpatient and inpatient services.

Study population

The study included patients diagnosed with hypothyroidism who were followed up in the department during the study period. The diagnosis was established based on clinical evaluation and biological confirmation (elevated serum TSH with or without reduced free T4 levels).

Inclusion criteria

- Adults aged 18 years and older

- Diagnosed with primary, secondary, or post-thyroidectomy hypothyroidism

- Under follow-up for at least three months

- Informed consent was provided to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria

- Patients with other major endocrine disorders (e.g., diabetes and Cushing’s disease)

- Patients with known severe psychiatric disorders diagnosed before hypothyroidism

- Patients are unwilling or unable to complete psychiatric assessment tools.

Sample size and sampling method

A non-probabilistic consecutive sampling technique was used. All eligible patients who attended consultations during the study period and met the inclusion criteria were recruited. The final sample comprised 40 participants.

Data collection

Data were collected through structured interviews and clinical examinations using a standardized questionnaire covering the following:

- Sociodemographic variables included age, sex, marital status, occupation, education level, and place of residence.

- Clinical variables: Type of hypothyroidism (primary, secondary, post-thyroidectomy), duration of disease, treatment adherence, and psychiatric history.

- Biological parameters: Most recent thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) values.

Assessment of anxiety and depression

Psychological symptoms were evaluated using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), a validated instrument widely used in medical populations.

- The HADS-anxiety (HADS-A) subscale was used to assess anxiety symptoms.

- The HADS-Depression (HADS-D) subscale assesses depressive symptoms. Each subscale contains seven items scored from 0 to 3, with total scores categorized as follows:

- 0–7: Normal,

- 8–10: Borderline (mild),

- ≥11: definite (moderate-to-severe).

A score ≥8 on either subscale was considered indicative of anxiety or depression.

Evaluation of treatment adherence

Adherence to levothyroxine therapy was assessed through patient self-report and prescription review, and categorized as follows:

- Regular,

- Irregular,

- Nonadherence (missed treatment for >2 weeks).

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of medical research. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants after explaining the study objectives and procedures. Confidentiality was strictly ensured at every stage, and no identifying personal information was collected. Participation was voluntary, with full respect to the dignity and autonomy of each participant.

Data processing and analysis

Data were entered and analyzed using Epi Info 7.0.

- Descriptive statistics (frequencies, means, and standard deviations) were used to summarise the patient characteristics.

- Chi-square (χ²) tests were used to assess the associations between categorical variables (e.g., anxiety/depression and sociodemographic or clinical factors).

- Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

Forty patients diagnosed with hypothyroidism were included in the study. The majority were female (90%), and only 10% male. The most represented age group was 40–59 years (47.5%), followed by 30–39 years (25%). Regarding professional activity, 60% were active and 40% were inactive. Most participants were married (52.5%), and 57.5% lived in urban areas (Dakar). Educational attainment was distributed as follows: 45% secondary, 32.5% university, and 22.5% primary (Table 1).

Prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms

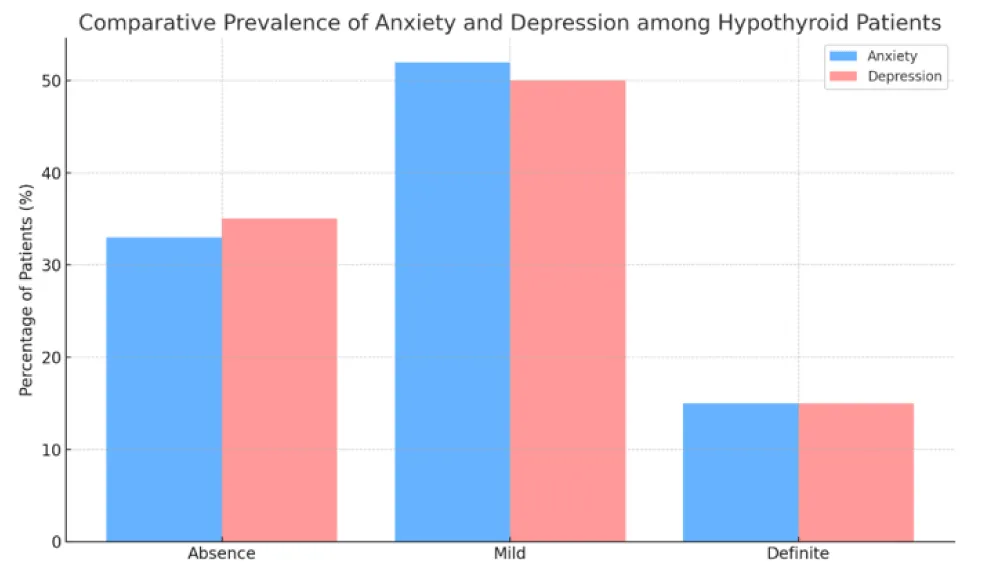

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) revealed a high prevalence of psychological symptoms among patients with hypothyroidism. The prevalence of anxiety was 67%, while depression affected 65% of participants. Mild symptoms were predominant in both conditions. Specifically, 52% presented with mild anxiety and 50% had mild depression. Severe (definite) symptoms were observed in 15% of patients in both conditions (Figure 1).

Factors associated with depression

Table 2 summarises the associations between sociodemographic and clinical factors and depressive symptoms. Depression was more frequent among inactive patients (81%), those with poor treatment adherence, and those with elevated TSH levels (> 4.5 mUI/L). This relationship was statistically significant for treatment adherence (p = 0.026), duration of follow-up (p = 0.031), and TSH values (p = 0.008). No significant associations were found with age, sex, or educational level.

Factors associated with anxiety

Anxiety was more common among inactive patients (52%), those with elevated TSH values (> 4.5 mUI/L), and irregular or nonadherent patients. This association was statistically significant for employment status (p = 0.037) and TSH levels (p = 0.037) (Table 3). No significant association was found with age, sex, or marital status.

Combined analysis

Depression and anxiety frequently co-occur with each other. Among the 40 patients, 52% presented with both symptoms simultaneously, 13% had isolated depression, and 15% had isolated anxiety. Only 20% of the participants had no symptoms (Table 4).

Summary

Psychological distress was highly prevalent among the patients with hypothyroidism in this sample. Elevated TSH levels, poor adherence, and longer disease duration were significantly associated with depressive symptoms, while unemployment and TSH elevation were correlated with anxiety. The overlap between these disorders underscores the importance of systematic mental health screening in endocrinology follow-up.

Discussion

Principal findings

In this cross-sectional sample of adults followed for hypothyroidism at a national referral center in Dakar, symptoms of anxiety (67%) and depression (65%) were highly prevalent in the HADS, with mild forms predominating and 15% meeting the “definite” threshold for each condition. Clinically, elevated TSH (>4.5 mUI/L) was associated with both anxiety and depression; nonadherence/irregular adherence and longer follow-up (>2 years) were linked to depression, whereas professional inactivity was linked to anxiety. Co-occurrence was common (52.5% screened positive for both), underscoring a shared vulnerability to hypothyroidism.

How our findings compare with prior literature

Our anxiety prevalence aligns with cross-sectional reports from India (63%), North Africa (≈62%), and the Balkans (~ 62%) using standardized scales, and sits above a large Chinese study reporting ~52% depending on the instrument and threshold [7-10,18]. Similarly, our depression prevalence (65%) approximates estimates reported in Indian and Maghrebi cohorts [7,9] and exceeds figures from Middle Eastern clinical samples (~32–34%), which likely reflects case-mix, thresholds, and cultural reporting patterns [19,20].

Consistent with a growing body of evidence, female sex showed higher crude proportions for both anxiety and depression in our data (not statistically significant), paralleling meta-analytic and cohort findings that women with thyroid dysfunction carry a greater affective burden [21,22]. Age patterns were not significant, echoing mixed results in the literature, where some studies suggested a U-shaped distribution with higher vulnerability in younger and older adults [23].

Correlates of anxiety and depression in hypothyroidism

The two signals are robust and clinically coherent.

- Thyroid control (TSH): Patients with elevated TSH levels had more anxiety (76% vs. 43%; p = 0.037) and depression (81% vs. 30%; p = 0.008). This mirrors data indicating a dose-response relationship between rising TSH and affective symptoms, even at “borderline” elevations [24]. Biologically, insufficient tissue T3/T4 in limbic and prefrontal circuits can disturb monoaminergic signaling, neuroplasticity, and HPA-axis dynamics implicated in mood and anxiety [5,6].

- Treatment adherence: Depression rose from 48% (regular) to 75% (irregular) and 100% (non-adherent) (p = 0.026), consistent with studies linking levothyroxine adherence to better mental health outcomes [15,25]. Persistent biochemical hypothyroidism due to poor adherence plausibly sustains the affective symptoms.

Additionally, professional inactivity was significantly associated with anxiety (52% vs. 30%; p = 0.037), in line with evidence that unemployment and socioeconomic stress heighten anxiety risk in chronic endocrine conditions [26,27]. In contrast, education, marital status, residence, and prior psychiatric history were not significant, although prior work has variably implicated these factors depending on context and measurement [20,28,29].

Comorbidity and clinical meaning

The high overlap (52.5%) between anxiety and depression reiterates that patients with hypothyroidism often present with mixed affective symptomatology, which can be missed if screening focuses on a single domain. Routine dual-domain screening (e.g., HADS-A/HADS-D) in endocrinology clinics is therefore warranted. Given the observed associations, prioritizing biochemical control of TSH and supporting adherence should be foundational, complemented by brief psychosocial interventions targeting work inactivity, financial strain, and couple conflict, where present.

Pathophysiological considerations

Thyroid hormones modulate serotonergic and noradrenergic systems, cortical excitability, hippocampal plasticity, and circadian regulation—pathways central to affective regulation [30-33]. Elevations in TSH, particularly when sustained, may reflect inadequate tissue thyroid signaling that lowers mood threshold and amplifies anxiety responsivity. This offers a mechanistic rationale for the strong TSH–mood link observed in this study.

Strengths and limitations

This study is among the first to examine the comorbidity of anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients with hypothyroidism in Senegal. This study contributes to filling a major gap in the sub-Saharan African literature by combining clinical, biochemical, and psychiatric data within the same cohort. The use of standardized scales, such as the HADS, adds methodological rigor.

However, several methodological limitations must be acknowledged.

First, the relatively small sample size (n = 40) reduced the statistical power and limited the generalisability of the results to the broader population of hypothyroid patients. Future studies with larger, multicentre, or longitudinal designs are needed to confirm these associations and explore the causal relationships.

Second, the use of a non-probabilistic consecutive sampling method may have introduced selection bias, as participants were recruited from patients regularly attending endocrinology follow-ups at a single tertiary hospital. This may limit the representativeness of the sample, particularly for individuals with limited access to specialized care.

Third, the analysis relied mainly on univariate statistical tests (chi-square), which restricted the capacity to control for potential confounding factors. Multivariate logistic regression would have allowed a more robust assessment of the independent predictors of anxiety and depression. Future research should integrate such models to strengthen the causal inference.

Finally, although this study reported statistically significant associations, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were not systematically calculated. Their inclusion in future analyses would enhance clinical interpretability and the strength of the evidence.

Implications and recommendations

- Embed systematic screening for anxiety/depression in hypothyroid follow-up (e.g., HADS or PHQ-9/GAD-7) with referral pathways to brief psychological care.

- Treat-to-target TSH and optimized adherence (education, pill-taking routines, pharmacy synchronization, SMS reminders) as first-line strategies to reduce affective symptoms.

- Address social determinants—particularly professional inactivity—via social work referral, graded return-to-work counseling, or community programs.

- Future research should deploy longitudinal designs and interventional trials to test whether TSH optimization and adherence support causally improve anxiety/depression trajectories and define thresholds where psychiatric risk rises steeply.

Conclusion

In this clinical cohort of adults with hypothyroidism in Dakar, anxiety (67%) and depression (65%) were highly prevalent in the HADS, with a substantial co-occurrence (52.5%). Beyond sociodemographic trends, three signals stood out: (i) biochemical imbalance—elevated TSH (>4.5 mUI/L)—was associated with both anxiety and depression; (ii) treatment adherence showed a graded relationship with depression (from 48% in regular adherers to 100% in non-adherent patients); and (iii) professional inactivity was associated with anxiety. These findings suggest that affective morbidity in hypothyroidism is closely linked to thyroid control and modifiable care processes rather than to immutable traits.

Clinically, endocrinology follow-up should routinely screen for both anxiety and depression (e.g., HADS/PHQ-9/GAD-7), optimize levothyroxine adherence, and treat TSH targets while addressing social determinants (notably, employment barriers). Given the cross-sectional design and modest sample size, causal inference is limited; however, the consistency and effect directions warrant prospective studies and interventional trials to test whether adherence support and biochemical optimization reduce psychiatric symptom burden. Integrating brief psychological care and adherence-enhancing strategies into hypothyroidism management may meaningfully improve patients’ well-being and overall outcomes.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the use of ChatGPT (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) and Paperpal (Cactus Communications, Mumbai, India) for language editing, grammar correction, and assistance in improving the clarity and readability of this manuscript. The authors confirm that all AI-generated outputs were reviewed, verified, and edited to ensure accuracy, originality, and compliance with ethical publication standards.

References

- Taylor PN, Albrecht D, Scholz A, Gutierrez-Buey G, Lazarus JH, Dayan CM, et al. Global epidemiology of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(5):301–16. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2018.18

- Chaker L, Bianco AC, Jonklaas J, Peeters RP. Hypothyroidism. Lancet. 2017;390(10101):1550–62. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30703-1

- Ogbera AO, Kuku SF. Epidemiology of thyroid diseases in Africa. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2011 Jul;15(Suppl 2):S82–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8210.83331

- Zimmermann MB. Iodine deficiency. Lancet. 2008;372(9645):1251–62. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(08)61005-3

- Bauer M. Thyroid hormones, T3 and T4, are in the brain. Thyroid. 2020;30(12):1733–45.

- Dayan C, Panicker V. Management of hypothyroidism with combination thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) hormone replacement in clinical practice: a review of suggested guidance. Thyroid Res. 2018;11:1. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13044-018-0045-x

- Bathla M, Singh M, Relan P. Depression in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2016;20(4):468–74. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8210.183476

- Trajanovska AS. Assessment of anxiety and depression in patients with hypothyroidism. Prilozi. 2021;42(2):29–36.

- Zaizoune I. Troubles anxiodépressifs et hypothyroïdie: Étude chez 37 patients au Maroc. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37:312.

- Dahesh T, Mosleh Shirazi MA, Dahesh P. Prevalence and associated factors of anxiety and depression among patients with hypothyroidism in South Iran. BMC Psychiatry. 2025;25(1):54. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-025-06490-3

- Peterson O, Johnson M, Williams R. Bidirectional relationship between hypothyroidism and mood disorders: a longitudinal study. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):782–91.

- Kim JS, Zhang Y, Wh WH. Subclinical hypothyroidism and meta-analysis: Journal of Affective Disorders and Mood Disorders. J Neuroendocrinol. 2019;245:91–8.

- Diagne N. Clinical and etiological aspects of hypothyroidism at Aristide Le Dantec Hospital. Afr J Endocrinol. 2012;2(1):14–8.

- Ndiaye A. Depression and hypothyroidism: an underestimated association in clinical practice in Senegal. Afr J Intern Med. 2021;8(1):12–9.

- Hennessey JV. Impact of levothyroxine adherence on mental health outcomes in hypothyroidism: a U.S. retrospective study. Endocr Pract. 2022;28(4):392–400.

- Bauer M. Psychiatric comorbidities and thyroid dysfunction: a clinical overview. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(4):290–300.

- Ogbera AO, Kuku SF. Epidemiology of thyroid diseases in Africa. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2011;15(Suppl 2):S82–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8210.83331

- Peng P, Wang Q, Lang X, Liu T, Zang XY. Association between thyroid dysfunction, metabolic disturbances, and clinical symptoms in first episode, untreated Chinese patients with major depressive disorder: undirected and Bayesian network analyses. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1138233. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1138233

- Mohammad MYH, Bushulaybi NA, AlHumam AS, AlGhamdi AY, Aldakhil HA, Alumair NA, et al. Prevalence of depression among hypothyroid patients attending the primary healthcare and endocrine clinics of King Fahad Hospital of the University (KFHU). J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8(8):2708–13. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_456_19

- Hamed A. Prevalence of depression among hypothyroid patients: the role of sociodemographic factors in Syria. Biomed Res. 2021;32(2):87–94.

- Chueire VB. Gender differences in psychiatric symptoms among hypothyroid patients: a meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2021;145:110464.

- Fan Y. Thyroid dysfunction and psychiatric comorbidity: a prospective cohort study in the UK Biobank. Psychol Med. 2024;[Epub ahead of print].

- Virgini S. Age-related U-shaped curve of depression prevalence in hypothyroid patients. Endocrinol Ment Health. 2023;20(4):167–75.

- Wyne KL. Thyroid function and psychiatric symptoms: the impact of TSH elevation. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2023;77(5):280–7.

- Jonklaas J. Thyroid hormone therapy and psychiatric symptoms: importance of adherence. Thyroid. 2023;33(1):12–21.

- Siegmann EM. Association of unemployment and anxiety: a meta-analytic review. J Affect Disord. 2018;232:176–84.

- Thomsen AF. Employment status and common mental disorders: the role of socioeconomic position. Psychiatry Res. 2019;272:1–8.

- Medici M. Social support and psychological outcomes in thyroid disorders: a population-based study. Thyroid. 2021;31(9):1372–80.

- Rodondi N. Loneliness and psychiatric symptoms among adults with thyroid dysfunction. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2020;113:104546.

- Bauer M, Whybrow PC. Thyroid hormone, neural tissue, and mood modulation. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2001;2(2):59–69.

- Bauer M, London ED, Whybrow PC. Thyroid hormone regulation of gene expression in the brain: relevance to mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27(2):228–42.

- Jackson IMD. The thyroid axis and depression. Thyroid. 1998;8(10):951–6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.1998.8.951

- Monteleone P, Maj M. Circadian endocrine rhythms in depression: a role for the clock genes? CNS Drugs. 2008;22(7):525–38.

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley